About Music for Early Film

Although we commonly call the films made between 1895 and 1927 “silent,” these works were almost universally accompanied by music and/or sound. In his 2013 report on the state of silent film preservation, David Pierce estimates that American filmmakers made nearly 11,000 silent feature films—a feature being define as any film that is four or more reels long—between 1912 and 1929.[1] Of these, only about twenty-five percent survive in some form today. After an early argument about whether motion pictures should have musical or other sonic accompaniment was settled by the overwhelmingly positive calls for music and sound by critics, audiences, and performers, new musical industries sprung up to serve the needs of cinemas and motion picture production houses.

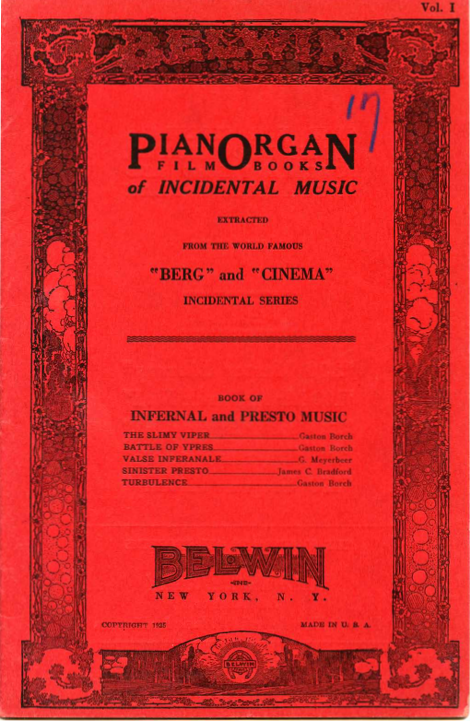

An example of a photoplay album. This volume of “Infernal and Presto Music” from Belwin contains four pieces for use in the cinema.

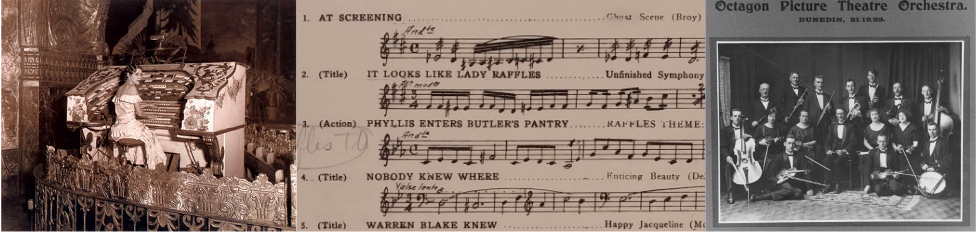

As Richard Abel, Rick Altman, Julie Hubbert, Martin Marks, and other scholars of silent film sound have documented, there were no standardized practices for supplying music for films. Music for accompanying films initially came from vaudeville music libraries, popular song, pre-existing art music, and original compositions, only some of which were committed to paper. In the 1910s, publications of music expressly for film accompaniment began to proliferate, offering what is called genre music or mood music for actions, events, and emotions commonly found in film scenarios. Using published collections of genre music, called photoplay albums, cinema pianists, organists, or ensembles could patch together a handful of pieces to create a compiled score of generic pieces that provided music that broadly matched the action on screen.

These pieces provide the earliest documentation for the use of musical mimesis in films. Works for “hurry” or “gallop” were quick in tempo, mimicked the sound of hoof beats or heartbeats, and employed short note values, all of which suggested the associated speed of motion given in the title.

In Motion Picture Moods, an enormous collection of generic pieces selected and arranged by film score composer and arranger Erno Rapée, “Aeroplane” is represented by Mendelssohn’s “Rondo Capriccio,” in which a three-measure passage of rapidly alternating thirds in the piano’s right hand is apparently meant to stand in for the sound of high-speed propellers; one entry for “Sea Storm” is Grieg’s “Peer Gynt’s Homecoming/Stormy Evening on the Coast,” which musically imitates choppy seas through the use of alternating low and high As in the bass in sixteenth notes.[2]

At the same time, some performers improvised throughout an entire film, created their own motifs to use for each picture they accompanied, and composed entire scores that often went undocumented or for which the creators’ notes are no longer available. Cinema organist Rosa Rio, for example, often had to accompany films without previewing them, so while she accompanied a movie for the first time, she worked to compose motifs or themes for the characters or events in the picture, upon which she would then improvise and elaborate in following showings, ultimately creating a consistent score that she would play from memory each time she accompanied the picture.[3]

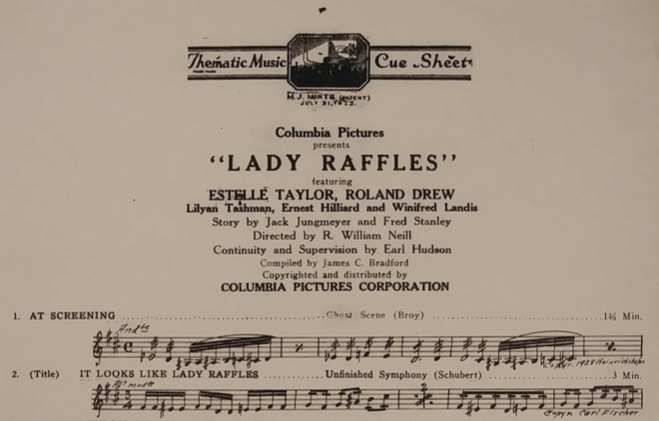

Other performers preferred to work from a list of suggestions for music, known as a cue sheet, which lists a film’s major events or cues next to the title or incipit of a piece that would go well with the action. As the demand for music for film grew, studios began issuing cue sheets for individual films, prepared by in-studio composers or score compilers. The Edison Film Company began issuing cue sheets with all of its feature-length films in 1913;[4] Mutual Film Company did so in 1917;[5] and other companies followed. Around the same time, film magazines also began publishing cue sheets created by the editors of their music columns or music departments.[6]

The title and first two cues for “Lady Raffles,” showing the melody lines for suggested music.

During the 1910s and early 20s, only the most prestigious films with the largest budgets received fully original, completely synchronized scores for their presentation in cinemas. These “special scores,” as they were marketed, generally eschewed pre-existing music of any kind, although some did include a single notable pre-existing theme or popular song, often for marketing purposes. The special score existed from the beginnings of film and film music; Nathaniel D. Mann composed the first such score for the 1908 film The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays.[7] As Martin Marks notes, the genre blossomed in the United States between 1910 and 1914, and more studios began producing full scores for their pictures.[8] The composers of these often applied a Wagnerian approach to scoring films, assigning leitmotivs to characters and places as a means of connecting all of the elements of the film through the music and developing a coherent musical narrative that was carried throughout the score.

Nonetheless, the completely original and synchronized score remained far from the norm. Of the full-length film scores produced during the late teens and early twenties, many remained compiled scores with only a few original sections: that is, they were comprised of pre-existing pieces that were connected to one another with original transitions and sometimes contained a new song or tune for a romantic or climactic scene. During the silent era, songs associated with individual movies were often sold as sheet music, on rolls for player pianos, or on records as a means of promoting the film and capitalizing on it beyond cinema ticket sales. Photoplay albums and single-work generic music and cue sheets continued to be used by most motion picture accompanists until the widespread coming of sound between 1927 and 1929, although original full scores became increasingly common as the 1920s progressed.

Even the terminology for film music was flexible. In a cue sheet, each individual action on screen that demanded new music was called a “cue.” But in full scores, “cues”—often numbered—ranged from a single short piece for a scene to a longer composite work that changed one or more times during its length and included numerous synchronization points—indicated by “D.” (for directions or actions on-screen) or “T.” (for text or title cards) markers in the score—within it. In films in which the director frequently used cuts, these composite cues were common. Music for film requiring externally-produced aural accompaniment continued to be written and published until about 1930, even though “talkies” had become the norm.

Sources

[1] David Pierce, “The Survival of American Silent Feature Films, 1912-1929” (Washington, D.C.: National Film Preservation Board, with the Council on Library and Information resources and The Library of Congress, 2013): 1, http://www.loc.gov/film/pdfs/pub158.final_version_sept_2013.pdf.

[2] Erno Rapée, Motion Picture Moods, for Pianists and Organists; [a Rapid-Reference Collection of Selected Pieces, Adapted to 52 Moods and Situations.] (New York: G. Schirmer, 1925): 2, 655.

[3] Weekend Edition Saturday, “Making the Music for Silent Movies,” NPR.org, accessed January 15, 2015, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5559593.

[4] “Edison Issues Music Cues.” Motography 10, no. 8 (October 18, 1913): 291.

[5] “Mutual to Provide Music Cue Service with Features.” Motion Picture News 15, no. 12 (March 26, 1917): 1847.

[6] Early cue sheets in magazines include those by Ernst Luz for Motion Picture News in 1915; George W. Beynon in Moving Picture World starting in 1919; and L. G. DelCastillo in American Organist in 1922.

[7] Eric Dienstfrey, “Synch Holes and Patchwork in Early Feature-Film Scores,” Music and the Moving Image 7, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 43. Mann’s score predates Camille Saint-Saëns’s score for L’assassinat du duc de Guise by just weeks.

[8] Martin Marks, Music and the Silent Film (Oxford University Press, 1997): 62.