SFSMA’s gotten a great review by Erin M. Brooks in The Journal of the Society for American Music! Download it as a PDF here, or read the full text below.

Journal of the Society for American Music (2020), Volume 14, Number 4, pp. 522–524

doi:10.1017/S1752196320000395

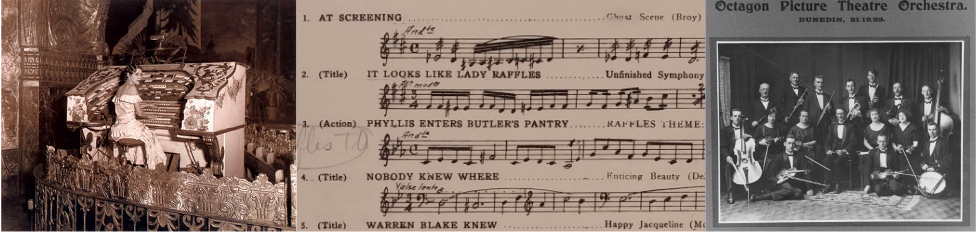

Silent Film Sound & Music Archive: A Digital Repository. https://www.sfsma.org In fall 1929, letters to the editor of Photoplay hotly debated pros and cons of the new “talkies.” Reactions ran the gamut, from a movie musician who claimed talkies would save her from apathetically “sawing through thousands of performances” to a spectator who expressed her intense annoyance with the new “canned music” replacing live theater organs and orchestras.[1] These exchanges offer a glimpse into the radical shifts in film music practice around 1930; prior to this, so-called “silent films” were accompanied by a huge variety of sounds, from generic mood music and cue sheets to compilation scores and original (“special”) scores.[2] As the movie industry transitioned to the sound era, many of these early musical resources were destroyed, stashed away, or gradually amassed in archives. Yet the work of silent film advocates, investments in silent film collections by research institutions, and the resurgence of silent film screenings accompanied by live music have all increased the prominence of silent film sound in recent years.[3]

The Silent Film Sound & Music Archive (hereafter SFSMA) preserves and disseminates music of the silent era (ca. 1895–1930). Established in 2014, SFSMA is headed by founder and executive director Kendra Preston Leonard, a musicologist whose work includes a focus on silent film music archives. Scholars specializing in a variety of film musics serve as SFSMA directors and officers. The archive is a 501(c)(3) organization supported by donations, ranging from individual and institutional gifts of silent film materials to operational grants from both people and

entities such as the Grammy Foundation and the Society for American Music. SFSMA’s nonprofit status underscores the archive’s mission to make silent film musics freely available to scholars, performers, and other individuals; all works are posted under an Open Data Commons Attribution license. The archive is very much an ongoing project. New materials continue to be uploaded to the website, usually announced via the News tab as well as SFSMA’s social media accounts.[4] To use the archive, visitors enter text into a search box to peruse by criteria such as composer/arranger/editor, title, date, publisher, and instrumentation. The search function also pulls up music associated with the various “moods” of silent film music; entering “hurry” or “misterioso,” for example, yields dozens of results. Users can likewise dip into different formats—such as sheet music or cue sheets—or browse tagged items. The music is well cataloged, typically with detailed bibliographic information and sometimes OCLC numbers.

As a cursory tour through a few SFSMA holdings, a 2016 “Sight and Sound” subvention from the Society for American Music funded twenty-five recordings by silent film accompanist Ethan Uslan.[5] The recordings, drawn from SFSMA sheet music, are excellent resources for class or public lectures. Other items assist performers by including orchestral parts (rare in most theater and film music collections).[6] Some works within the archive are heavily marked with performance indications, offering insight into silent film performance practice. Items from specific performers, such as cinema accompanists Claire Hamack and Adele V. Sullivan, offer tantalizing research opportunities; these collections both highlight the central role of women as motion picture accompanists and invite case studies of individual musicians and theatrical scenes. Indeed, while SFSMA broadly focuses on preserving printed music, the archive’s rich materials assist with crafting historiographies focusing on gender, sexuality, race, and class. Moreover, archive holdings provide a refreshingly decentralized view of film music in the United States through examples from places other than New York or Chicago.[7]

The archive is aimed at a broad swath of users, including researchers, performers, and educators. There is a small amount of specifically pedagogical content, from a guide to citing the archive to a short essay on music for silent film. The archive’s research value is abundantly clear, and it is likewise easy to envision students using materials from the archive. The pedagogical utility could be expanded, how- ever, by adding a tab with additional guidance for newcomers to silent film music— many users may need more help in deciding what to search for or in comprehending the context of collections such as Erno Rapee’s Encyclopedia of Music for Pictures or the four-volume Sam Fox Moving Picture Music.

There is plenty of potential to expand the archive. Although the recordings by Uslan are a good resource, increasing video and audio materials seems both a natural fit for silent film and a means of increasing the attractiveness of the site. Continuing to add images, multimedia posts, and essays would greatly enhance the overall user experience of this excellent repository. Such projects may already be underway; the webpage notes initial work in digitizing period recordings ofSFSMA sheet music holdings. Of course, adding to the site necessitates donations of materials, money, and time. Hopefully SFSMA will attract a burgeoning number of individuals and organizations willing to support this work. An expansive, openly-accessible online archive of silent film scores would be an incredibly valuable resource. Although its digitized collections already showcase a compelling sample of silent film sound, SFSMA has the potential to serve as a pivotal gateway to this material if the repository continues to grow and forge partnerships with other institutions.

Erin M. Brooks

Notes

[1] “Brickbats and Bouquets,” Photoplay, August 1929, 10, and September 1929, 142. These were by no means the only viewpoints; later that fall Photoplay published a letter from a theater organist heartily defending his profession.

[2] Many scholarly works discuss early film accompaniment styles in detail; for example, see Martin Miller Marks, Music and the Silent Film: Contexts and Case Studies, 1895–1924 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

[3] For a summary of archival resources for silent film music, see Kendra Preston Leonard, “Using Resources for Silent Film Music,” Fontes Artis Musicae 63, no. 4 (October–December 2016): 259–76, or the longer guide in Leonard, Music for Silent Film: A Guide to North American Resources (Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2016).

[4] SFSMA has an active presence on Facebook and Twitter. These accounts regularly feature posts on both the archive and other news related to silent film music. The Twitter feed is also accessible as a sidebar on the SFSMA website.

[5] For more information, see Kendra Leonard, “New Audio Recordings by Ethan Uslan,” Silent Film Sound & Music Archive, last modified July 26, 2016, https://www.sfsma.org/ARK/22915/new- audio-recordings-by-ethan-uslan/.

[6] For example, see roughly three hundred pieces and around 2,300 instrumental parts within The Silent Cinema Presentations, Inc./Ben Model collection, digitized thanks to a grant from the Grammy Foundation. On how to locate these items, see From the Director, “New Posts Going Up,” Silent Film Sound & Music Archive, last modified October 13, 2016, https://www.sfsma.org/ARK/22915/new- posts-going-up/.

[7] At the moment, SFSMA seems to primarily include sources connected to the United States film industry. Problems with a narrow focus on New York (“gothamcentrism”) in theater or film studies have been discussed by Robert C. Allen, “Decentering Historical Audience Studies: A Modest Proposal,” in Hollywood in the Neighborhood: Historical Case Studies of Local Moviegoing, ed. Kathryn H. Fuller-Seeley (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 20–33.